Did Winston Churchill suffer a heart attack in the White House?

At ten o’clock on the night of December 27, 1941, Dr. Charles Wilson received an urgent message. Dr. Wilson, who was in Washington as Winston Churchill’s primary physician, was asked to rush to White House at the request of the Prime Minister. When Wilson arrived, his celebrated patient shared a serious medical concern:

“It was hot last night and I got up to open the window. It was very stiff, I had to use considerable force and I noticed all at once that I was short of breath. I had a dull pain over my heart. It went down my left arm. It didn’t last very long, but it has never happened before.”

After a cursory examination, Wilson determined that “whether the electro-cardiograph showed evidence of a coronary thrombosis or not, his symptoms were those of coronary insufficiency.”

Wilson then faced a major dilemma. “The textbook treatment for this is at least six weeks in bed. That would mean publishing to the world … that the P.M. was an invalid with a crippled heart and a doubtful future. And this at a moment when America has just come into the war, and there is no one but Winston to take her by the hand. I felt that the effect of announcing that the P.M. had had a heart attack could only be disastrous. I knew, too, the consequences to one of his imaginative temperament of the feeling that his heart was affected. His work would suffer. On the other hand, if I did nothing and he had another and severer attack – perhaps a fatal seizure – the world would undoubtedly say that I had killed him through not insisting on rest.”

Churchill pressed Wilson for an instant diagnosis. “Is my heart all right?”

“There is nothing serous. You have been overdoing things…. You needn’t rest in the sense of lying up, but you mustn’t do more than you can help in the way of exertion for a little while.”

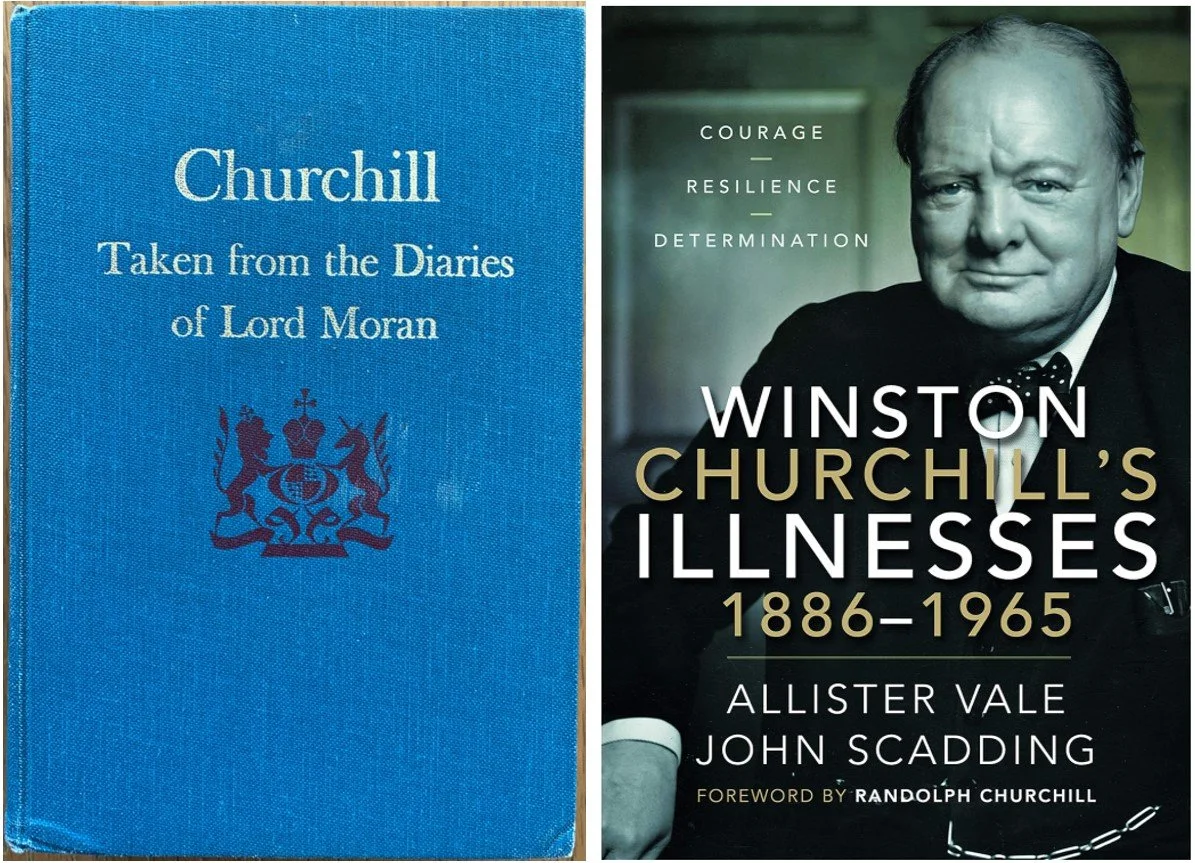

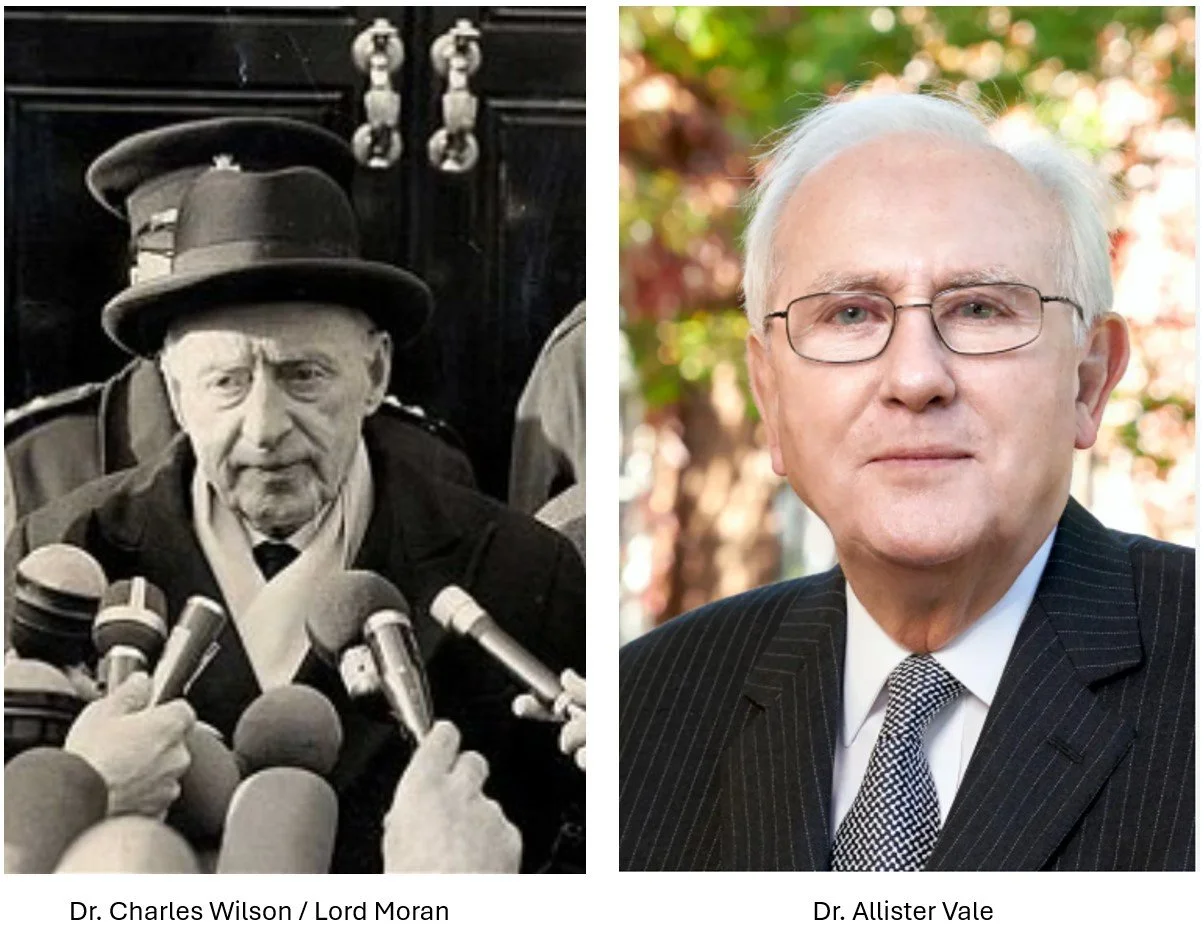

Not only did Churchill disregard Wilson’s prescription for limited exertion, he was, of course, a force of nature through the end of the war four years hence, and he lived another twenty-three years. Dr. Charles Wilson, who served Churchill through the end of his life, was granted a peerage by King George VI in 1943, and became First Baron Moran. He was commonly known as Lord Moran from that point forward.

Winston Churchill’s heart attack at the White House became part of historical lore, and is mentioned in most Churchill biographies. But as I recently learned, that heart attack never occurred.

The most fascinating presentation that I attended at last month’s International Churchill Conference in Washington DC was titled: “Did Winston Churchill suffer a heart attack in Washington DC?” In a 45-minute talk that was more of a cloak and dagger account than a clinical analysis, Dr. Allister Vale - the co-author of Winston Churchill’s Illnesses: 1886-1965 - conclusively proved that Lord Moran’s account was false. In addition to electro-cardiogram images taken at several stages of Churchill’s life, Dr. Vale used Churchill’s vigorous schedule during the three weeks that directly followed his episode of chest pain (the pain was real!) to reinforce the unlikelihood of the 67-year-old Churchill having suffered a heart attack.

Lord Moran’s account of Churchill’s heart attack appears in the published version of his diaries – which ignited a furor, particularly within the Churchill family – as a violation of patient-doctor confidentiality. Remarkably, investigations by Dr. Vale and other physicians revealed that Lord Moran never kept a proper diary. Also, a number of events that he wrote about did not tie to well-documented records. In Moran’s near-contemporaneous notes from the infamous late night meeting in the White House, he mentioned Churchill’s chest pain, but said nothing about the pain passing down his left arm. This appeared to be a retroactive insertion to support the story of a heart attack … for reasons unknown. I’m not doing justice to Dr. Vale’s presentation in which me made a positively spellbinding case against Lord Moran.

On the second morning of the ICS conference, a short time after I took my seat for the buffet breakfast, someone asked if the seat next to me was open. That “someone” happened to be the delightful Dr. Allister Vale. I told him how much I enjoyed his talk, and he shared several fascinating and delightful insights about his research. When I returned home, I sent him an email in which I reiterated my appreciation, and also mentioned that I had ordered his book. (As luck would have it, Winston Churchill’s Illnesses: 1886-1965 arrived today). The signature lines in my email include a link to my website. Dr. Vale replied the next day with a very kind note in which he mentioned that he has preordered my book.

The moral of this story is, of course … if you ever have the opportunity to attend the International Churchill Society’s annual conference, don’t pass it up. The next conference will held in Philadelphia in October 2026.

Thanks for reading,

Bill

P.S. My friend Tom Whelan made the great suggestion that I also post these important warning signs and potential symptoms of a heart attack:

Chest Pain:

Tightness, squeezing, or pressure in the chest that may last for several minutes or come and go

Pain that radiates to the arm, neck, jaw, or back

Shortness of Breath:

Difficulty breathing, even with mild exertion

Feeling like you can't get enough air

Other Symptoms:

Nausea or vomiting

Sweating

Dizziness or lightheadedness

Fatigue

Anxiety

Numbness or tingling in the arm or leg

Additional Warning Signs in Women: Pain or discomfort in the upper back or shoulder, Indigestion or heartburn, and Unusual fatigue.